1,350.00 €

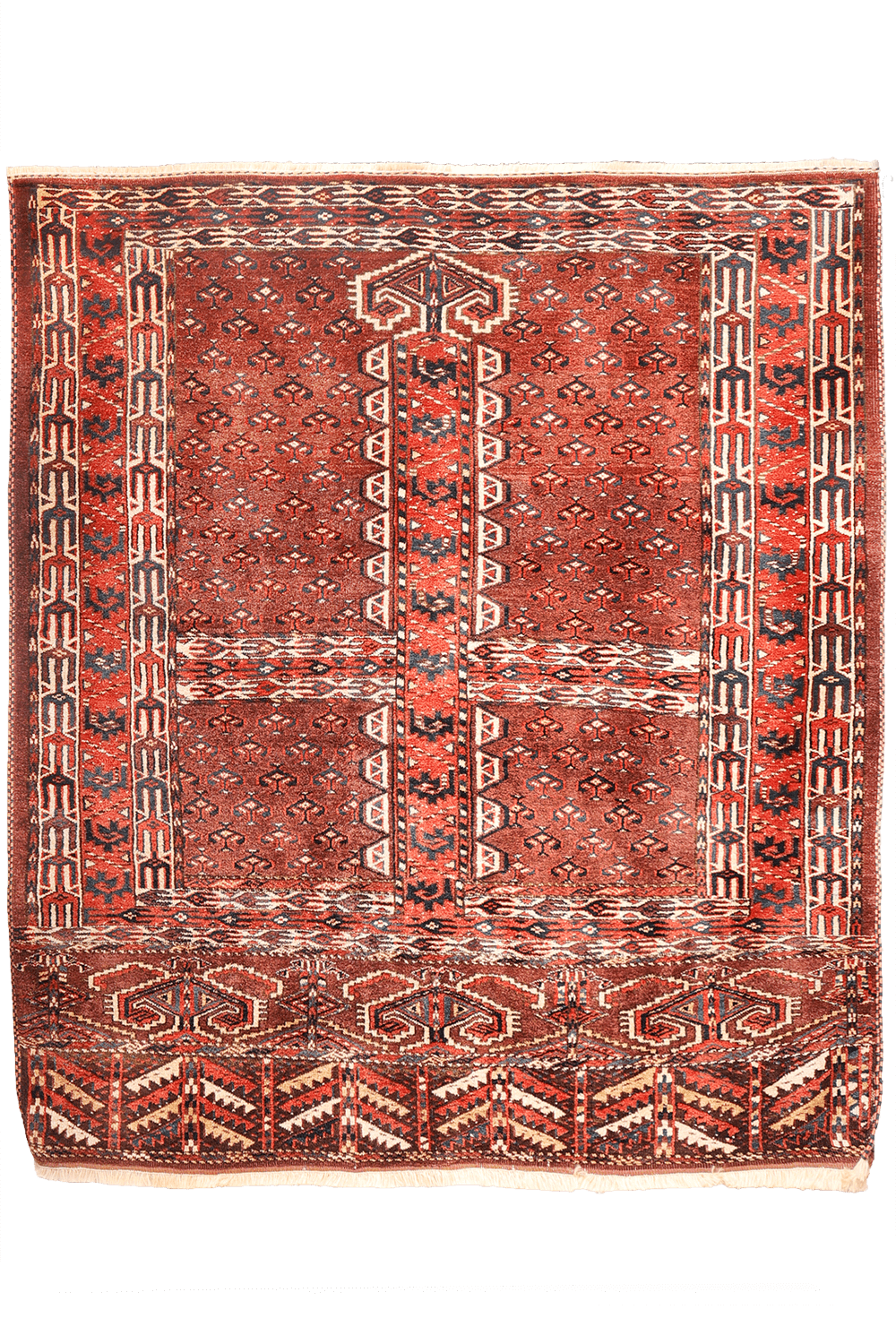

Fine Antique Turkmen Ensi (Yurt Door Rug)

A very finely woven Ensi or yurt door rug, as can be appreciated from its detailed design. An Ensi (also spelled Engsi) is a traditional Turkmen weaving originally used as a door hanging at the entrance of a yurt. Characterized by its rectangular format divided into panels—often four—, Ensi rugs typically display geometric motifs, rich shades of red and blue, and finely spun wool.

This particular piece is exceptionally finely knotted, featuring the traditional motifs of the Yomut tribe. The main field is divided into four compartments of varying sizes, while the lower section showcases a broad “skirt” or border, typical of classic Ensi designs. All dyes are 100% natural, and the wool is of superior quality.

Material: 100% hand-spun sheep wool

Size: 165×149 cms

Origin: Yomut, Afghanistan/Turkmenistan

Date of weaving: 1920s

The special carpet with its unmistakable design which was used solely as a closure to a yurt is called purdah (or curtain) in Afghanistan. In the USSR, it is called ensi and in Iran, generally hatchlu.

This carpet has a fringe at the bottom and a cord at each corner, sometimes of goat hair, at the top for tying to the wooden frame of the yurt. The purdah design has become very popular and is now also executed in carpet form, that is, larger than the traditional purdah of the yurt, and with fringes at both ends.

The overall design usually consists of a wide vertical and horizontal band in the form of a cross separating the centre field into four panels. Following the old tradition, each panel usually displays the candlestick motif in one of its many interpretations. In new Afghan pieces, the secondary motifs in both

borders and ends often denote the clan to which the weaver belongs. Though significantly absent, in old pieces, in many purdahs the two segments of the vertical band come to a point, suggestive of a mihrab, or prayer niche. It is this that may have given rise to the belief that purdahs were used as prayer mats. Although opinions are divided, the author’s view is that it was most unlikely that a purdah was a dual-purpose carpet. Apart from the sheer tedium of untying and retying the purdah five times a day, it is difficult to believe, even assuming that the yurts are pitched away from the prevailing winds, that the interior would be left exposed to the frequent and violent sand and wind storms while the inhabitants make their devotions on the front door. Moreover, I have never met a Turkoman who admitted to saying his prayers on a purdah. It is far more probable that the appearance of this so-called mihrab, now so common, was the result of a normal evolution of this art – perhaps inspired by the weaver’s piety. Some say that the cross is a reproduction of a wooden door panel. There is not much credence to this theory as most yurt doors have no panels.

Purdahs are woven by Ersari Turkomans in large parts of Afghan Turkestan, though only very rarely in Daulatabad and Andkhoy. The finest purdahs undoubtedly come from Keldar, a small town on the Amu Darya River due north of Tashkurghan, and it is probably the purdahs woven by the Sulayman clan which take pride of place. For quite a while, most of the Keldar production was sold in Mazar and bought up by a single dealer.

“The carpets from Afghanistan”, R.D. Parsons

1 in stock

Additional information

| Weight | 6.8 kg |

|---|

Subscribe and receive the lastest news