1,200.00 €

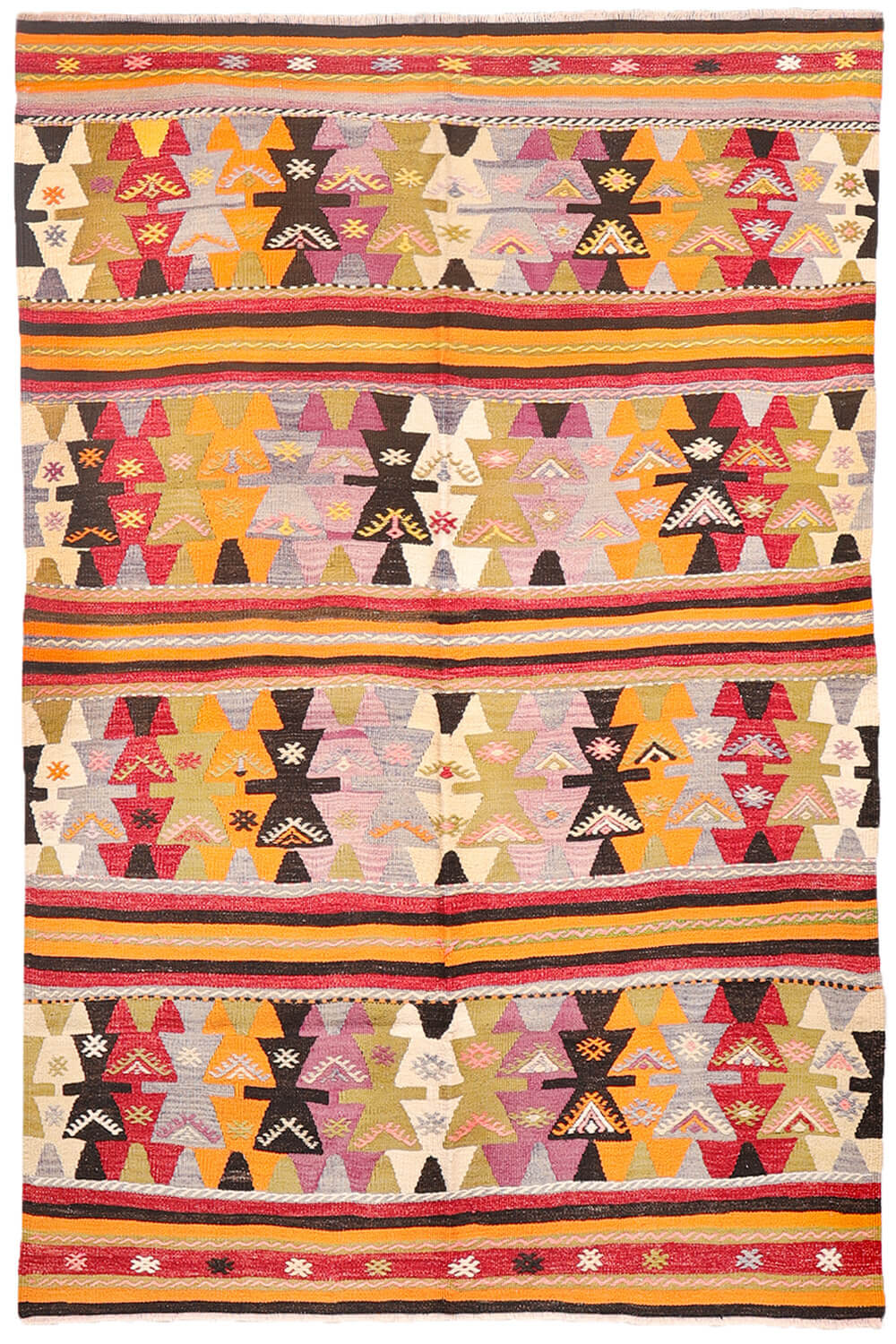

Vintage Konya Kilim with Horizontal Bands and Fertility Symbols

This striking vintage Konya kilim is composed of horizontal bands and rich in fertility symbolism.

The main motif throughout the piece is the triangle, a feminine symbol deeply rooted in ancient tradition. The weaver has superimposed pairs of triangles in the same colour to form a stylised female figure with outstretched arms, known as Elibelinde (literally “hands on hips”), also associated with the Mother Goddess. Elibelinde is one of the most powerful and enduring fertility symbols found in Anatolian kilims.

Here, the weaver has rendered the Elibelinde in a charmingly naïve and expressive manner. The kilim is further decorated with motifs executed in the cicim technique. On the chest of the figure, she added a cicim ornament in the shape of a pıtrak (thistle), another traditional feminine and fertility symbol.

Since prehistoric cave paintings (circa 15,000 BC), the female vulva has often been symbolised as a triangle. In this kilim, that reference may appear in the embroidered and decorated triangles forming the figure’s skirt—or perhaps in the lower triangles themselves, open to interpretation: are they her legs, or a vulva, a more direct fertility symbol?

This kilim was woven without a border, allowing the motifs to appear as if they extend beyond the edges of the textile, creating a sense of continuity. It is thick and robust, making it ideal for high-traffic areas. The white and black sections are woven in undyed natural wool.

Material: 100% hand-spun sheep wool

Size: 218×144 cms

Origin: Konya, Turkey

Date of weaving: 1970s

Elibelinde – “Hands on Hips”

Elibelinde, in Turkish, literally means “hands on hips.” This motif represents a pregnant woman standing in that posture to relieve the weight on her back. In many of the tribes and most of the villages we visited, we observed this major symbol of fertility—one of the three great concerns reflected in kilim iconography, alongside fecundity and protection.

The widespread presence of the “hands on hips” motif in Anatolian weaving links it directly to the Mother Goddess, the central deity of the proto-urban site of Çatalhöyük (7000 BCE), where many figurines depicting her have been unearthed—sculpted from clay or painted on walls.

While the myth of the Mother Goddess appeared as early as the Paleolithic era (30,000–20,000 BCE), particularly in southwest France, the Rhine Valley, Malta, and even Siberia, it seems to mark the shift from the wandering life of hunter-gatherers to the more settled or nomadic lifestyle associated with agriculture and herding. The Mother Goddess symbolizes not only human fertility but also the fecundity of the nourishing earth.

Primitive Matriarchy

Every visit we made to Anatolia’s nomadic communities felt like stepping back in time. Little has changed in their way of life since the early days of pastoral nomadism, which emerged over five thousand years ago. What always struck us was the prominent—often surprising for the Muslim world—position of certain women. It’s a living echo of the ancient matriarchy that once centered on the Mother Goddess.

Even recently, in the small town of Avanos, in Cappadocia, one could witness a rainmaking ritual held during severe droughts: a robust woman named Afife, known to all as Afife Aba (“Mother Afife”), would walk through the streets with a sieve on her head. From their windows above, villagers would pour jugs of water over her. Her size symbolized fertility, and the water symbolized fecundity—two key themes of the old Mother Goddess cult.

Finally, it’s worth noting that elibelinde is the only traditional anthropomorphic motif found on kilims. In primitive societies, only the Mother Goddess was depicted in human form. This provides yet another clear and indisputable link between this motif and its ancient origin.

Pıtrak or thistle

In Turkish, pıtrak is a motif said to originate from an ideogram stylizing the sun, without which plants could not grow. However, this origin has been forgotten over the centuries, and the motif has been passed down orally under a name inspired by something familiar to pastoral peoples: the small thistle well known to weavers, who spend hours removing it from the wool before spinning.

Does this mean that pıtrak, which refers to a plant whose burrs cling to clothing and, above all, to animal hair—especially sheep’s fleece—is not linked to an ancient myth or belief? In rural circles, the Turkish expression “pıtrak gibi,” literally “like thistle,” meaning “as abundant as thistle,” seems to support this idea: the thistle would be nothing more than a representation of the plant from which it takes its name, symbolizing fertility—like the ear of wheat or the pomegranate—simply because of its vegetal nature.

A Solar and Feminine Representation

This other observation, which brings us back to the sun, suggests otherwise: near Ankara, at the Hittite site of Alacahöyük, ritual bronze solar standards dating from the second half of the third millennium BCE have been unearthed, bearing a “thistle” similar to the one found on kilims. As we noted in relation to the lozenge symbol, the Anatolians regarded the sun as a feminine celestial body.

Pıtrak would therefore indeed be a solar representation: the center of the lozenge-shaped motif would express its feminine nature, while the radiating lines would depict its shimmer—often compared to the radiance of a woman.

From “symbolique des kilims” by Ahmet Diller

1 in stock

Additional information

| Weight | 5.9 kg |

|---|

Subscribe and receive the lastest news